Astronomers spot white dwarf that guzzled a Pluto-like world

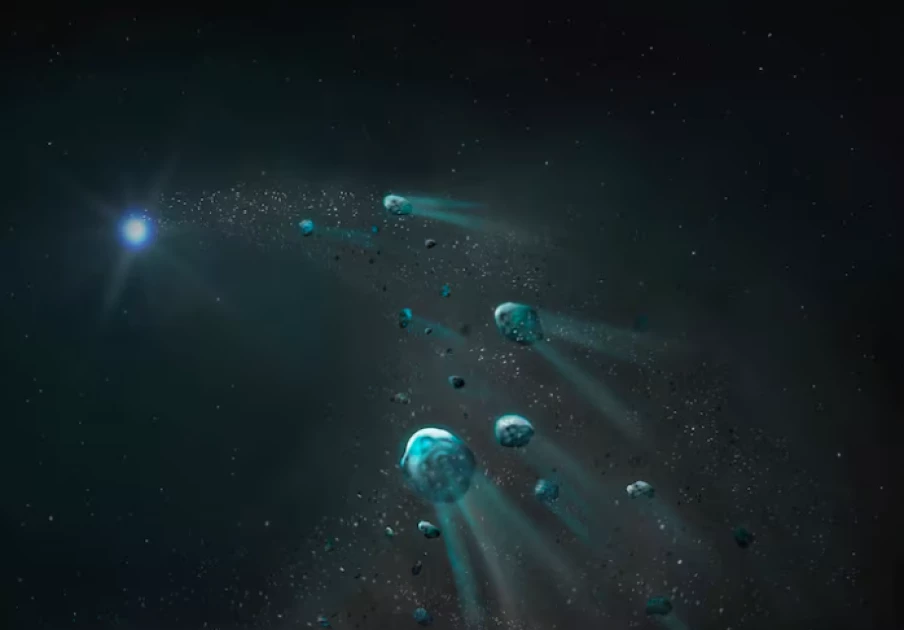

An early stage of an icy body being torn apart by the intense gravity of a white dwarf -a highly compact stellar ember- leaving glowing trails of gas and dust, as its fragments spiral inward, is seen in this handout illustration released on September 24, 2025. Snehalata Sahu/University of Warwick/Handout via REUTERS

Audio By Vocalize

Astronomers using the Hubble

Space Telescope have observed a white

dwarf - a highly compact stellar ember - that appears to have gobbled

up an icy world akin to the dwarf

planet Pluto, a finding with implications regarding the likelihood of

habitable planets beyond our solar system.

The white dwarf is located in our Milky Way galaxy about 255 light-years from Earth, relatively close in cosmic terms, and has a mass about 57% that of the sun. A light-year is the distance light travels in a year, 5.9 trillion miles (9.5 trillion km).

White dwarfs are among the universe's most compact objects,

though not as dense as black

holes. Stars with up to eight times the mass of the sun appear destined to

end up as a white dwarf. They eventually burn up all the hydrogen they use as

fuel. Gravity then causes them to collapse and blow off their outer layers in a

"red giant" stage, eventually leaving behind a compact core - the

white dwarf.

The sun appears fated to end its existence as a white dwarf,

billions of years from now. The white dwarf in the new study is a remnant of a

star estimated to have been 50% more massive than the sun. In its current

compact form, its diameter is roughly equivalent to that of Earth despite being

perhaps 190,000 times more massive than our planet.

Astronomers previously documented how white dwarfs, thanks

to their strong gravitational pull, consume - or accrete, in scientific terms -

rocky bodies like planets, moons and asteroids. Scientists use telescopes to

spot material on the white dwarf's surface made up of the elements that

comprised these objects.

Researchers have now detected a chemical fingerprint in this

white dwarf indicating that the object it swallowed was not primarily rocky but

instead icy. They suspect the white dwarf's gravitational effects ripped apart

a Pluto-like world and that its pieces then plunged onto it.

"The white dwarf likely accreted fragments from the

crust and mantle of a Pluto-like icy world," said Snehalata Sahu, a

postdoctoral research fellow in astrophysics at the University of Warwick in

England, lead author of the study published this month in the journal Monthly

Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, opens new tab.

"If not an entire Pluto, it would be a fragment chipped

off a Pluto-like world by the collision with some other body. Either way, once

this body gets sufficiently close to the white dwarf, roughly within a distance

comparable to the size of the sun, the strong gravity would tidally distort the

body, and it eventually would crack and disintegrate," said University of

Warwick astrophysicist and study co-author Boris Gänsicke.

Chemical evidence indicated that the object was not a comet,

another type of icy body.

"The key evidence comes from the unusually high

abundance of nitrogen we observed, much higher than in typical cometary

material, and consistent with the nitrogen-rich ices that dominate Pluto's

surface," Sahu said.

The detection of nitrogen, according to Gänsicke, was made

possible through the use of Hubble's Cosmic Origins Spectrograph instrument,

which observes ultraviolet light to study the formation and evolution of

galaxies, stars and planetary systems.

The rate of material falling onto the white dwarf was

equivalent to about the mass of an adult blue whale diving onto it every second

and sustained for at least the past 13 years, Sahu said.

These observations provided evidence that icy bodies like

those in our solar system exist in other planetary systems. The solar system

has an abundance of them, particularly in a frigid region beyond the outermost

planet Neptune, populated by dwarf planets like Pluto, comets and other icy

bodies.

Water is a crucial ingredient for life. But how

rocky planets like Earth come to possess large amounts of it is a matter of

debate.

"In our solar system, icy bodies such as comets are

thought to have played a key role in delivering water to the rocky planets,

including Earth. Along with water, they also supplied other volatile and

organic compounds such as carbon, sulfur and complex organics that are essential

for prebiotic chemistry and, ultimately, the emergence of life," Sahu

said.

"Similarly, in other planetary systems, water-rich

bodies are expected to serve as carriers of these fundamental building blocks,

potentially contributing to the development of habitable environments,"

Sahu added. "Detecting water-rich bodies around other stars provides

observational confirmation that such reservoirs exist beyond our solar

system."

Leave a Comment