OPINION: The hidden toll of maternal mortality in Kenya

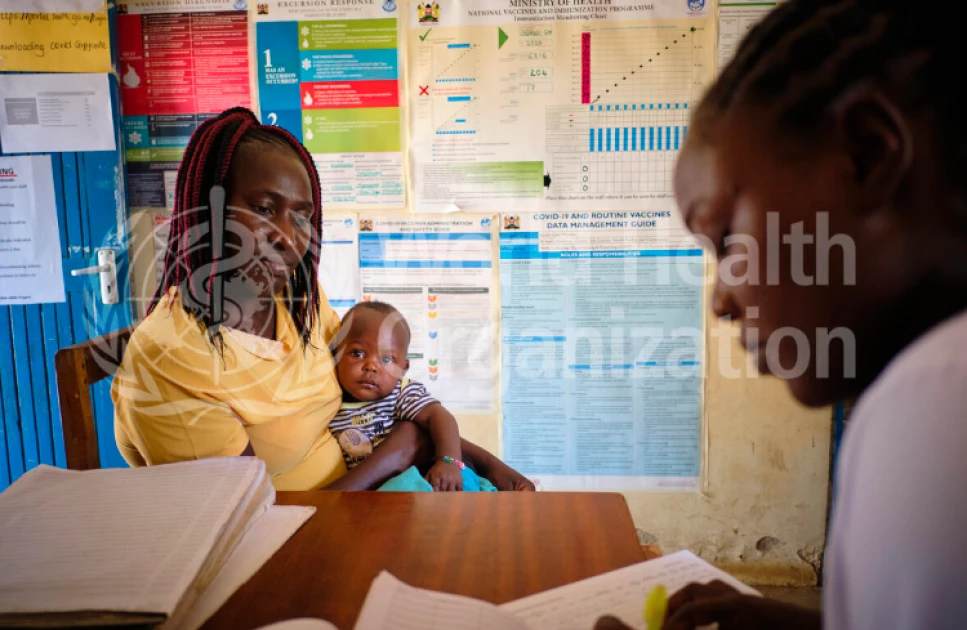

© WHO / Fanjan Combrink. A health worker fills in the Mother and Child booklet for Sarah and her 6-month-old grandson Adriane at the Chemelil Gok Health Centre in western Kenya.

Audio By Vocalize

Behind every maternal death in Kenya is a family forever changed. Children lose mothers, communities lose leaders, and the country loses potential.

At a recent Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child, and Adolescent Health and Nutrition (RMNCAH+N) high-level Policy Dialogue and CSO Roundtable in Nairobi, these stories and statistics came into sharp focus.

With less than five years to the 2030 Sustainable Development Goal targets, the two-day convening was an opportunity to accelerate reforms, strengthen accountability, and mobilize political will so every woman, child, and adolescent can thrive.

The Context of Women’s Health in Kenya

Kenya continues to face unacceptably high maternal mortality, with 355 deaths for every 100,000 live births. This translates to around 6,000 preventable deaths each year — about 16 women dying every single day. To put this in perspective: the loss of mothers in Kenya is the equivalent of a deadly matatu crash happening every single day.

Postpartum haemorrhage (PPH), the loss of 500 ml of blood after childbirth, the equivalent of a standard water bottle — remains the single largest cause of maternal deaths worldwide, disproportionately affecting women in low- and middle-income countries and the leading cause of maternal mortality in Africa.

In Kenya, PPH is the leading cause of maternal mortality (40%), followed by obstructed labor (28%), and eclampsia (14%) according to the Kenya Health Information System and significantly contributes to newborn asphyxia, a leading cause of neonatal mortality.

With universal access to family planning, quality antenatal and intrapartum care, skilled birth attendance, and emergency obstetric and newborn care (EmONC), most maternal and newborn deaths could be prevented.

Beyond antibiotics and oxytocics, procurement of recent innovations like heat-stable carbetocin for preventing postpartum hemorrhage and tranexamic acid (TXA) for timely bleeding management is essential. Safe blood transfusions also remain critical, yet many facilities still lack supplies, equipment, and trained staff.

Scaling up proven solutions—such as the E-MOTIVE approach, point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) for early detection of complications, and CPAP for newborns with respiratory distress—alongside stronger referral systems and reliable supply chains, could transform outcomes.

But even still, facility readiness and antenatal care remain uneven. The 2022 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey (KDHS, 2022) shows that over one-third of pregnant women do not attend four antenatal visits, with stark inequalities: only half of women with no education reach this minimum compared to more than eight in ten with higher education. Persistent socioeconomic divides, health worker shortages, weak referral systems, and inequitable financing further hold back progress.

Kenya’s health reforms toward primary health care and universal coverage have come with disruption. The shift from the Linda Mama program under NHIF to the new Social Health Insurance Fund (SHIF) has left gaps in access, with maternity services once free, now requiring out-of-pocket payments. Early signs suggest skilled birth attendance is declining as a result, putting mothers and newborns at greater risk.

Figures mask the daily reality: most deaths are preventable, and many could be linked to unintended or poorly supported pregnancies.

Participants highlighted that behind Kenya’s maternal mortality statistics lies a hidden driver: unintended pregnancies. They emphasized that without addressing access to contraception and prevention, maternal deaths will remain unacceptably high.

As asked by Hon. Dr James Nyikal, Chair of the National Health Committee, “How many of these deaths are actually coming from a planned pregnancy, and how many are coming from pregnancies that were not desired? There are a lot of maternal deaths that could be avoided by proper contraception.”

Youth voices underscored the hidden trauma of unintended pregnancies and early, unwanted motherhood. Teenage pregnancy rates remain stubbornly high at 15% with substantial county variation – and still persistent worrying trends with continued child marriage. Behind these numbers lie stories of young women forced to leave school, face stigma, or endure motherhood without support — a cycle that perpetuates poverty and poor health.

While Kenya has made progress, with unmet need for family planning declining from 27% in 2003 to 14% today, disparities between counties remain stark. More than one in four women in West Pokot (30%), Samburu (29%), Siaya (27%), and Isiolo (27%) still lack access, compared with less than 5% in counties such as Laikipia and Embu, according to the latest KDHS.

These figures, however, are in contrast with the Constitution of Kenya (2010) enshrines the right of every person to the highest attainable standard of health, including reproductive health and the right to life.

Speaking at the Global Leaders Network high-level side event on the margins of the United Nations General Assembly this week, President William Ruto reaffirmed Kenya’s commitment to universal health coverage and sustainable financing, declaring: “The future of Africa health financing lies in our own hands.”

The time to act is now

Kenya has a chance to act. The Maternal, Newborn and Child Health Bill 2023, currently before Parliament, would enshrine access to equitable, quality MNCH services in law and strengthen coordination between national and county governments. For this promise to translate into action, the bill must be urgently prioritised, championed across parties, and advanced without delay.

As Ministry of Health’s Head of RMNCAH, Dr. Edward Serem, reminded us, “With all these investments, women are still dying, children are still dying. We still need to put more efforts.” The time to act is now. The Maternal Health Bill offers an opening and we have legislation and commitments to ensure reaffirming Kenya’s commitment to health. But action must be scaled and sustained.

The toll of maternal mortality is measured not only in lives lost but in futures cut short and communities burdened with unspoken grief. Kenya has the knowledge and tools to change this. What is required now is decisive leadership, bold investment, and collective resolve.

As Kenya prepares to host the International Maternal Newborn Health Conference in 2026, we cannot welcome the world while losing the equivalent of a matatu full of mothers every day. The fire must keep burning—until women, girls, and children can live and thrive with dignity.

Dr. Margaret Lubaale is the Executive Director of Health NGOs Network (HENNET) and Lisa Mushega is the Collaborative Advocacy Action Plan (CAAP) Focal Point and Legal Policy Expert at HENNET, a PMNCH partner in Kenya.

Leave a Comment