US-Kenya health deal: The data privacy concerns, America’s soft power and Kenya’s stake

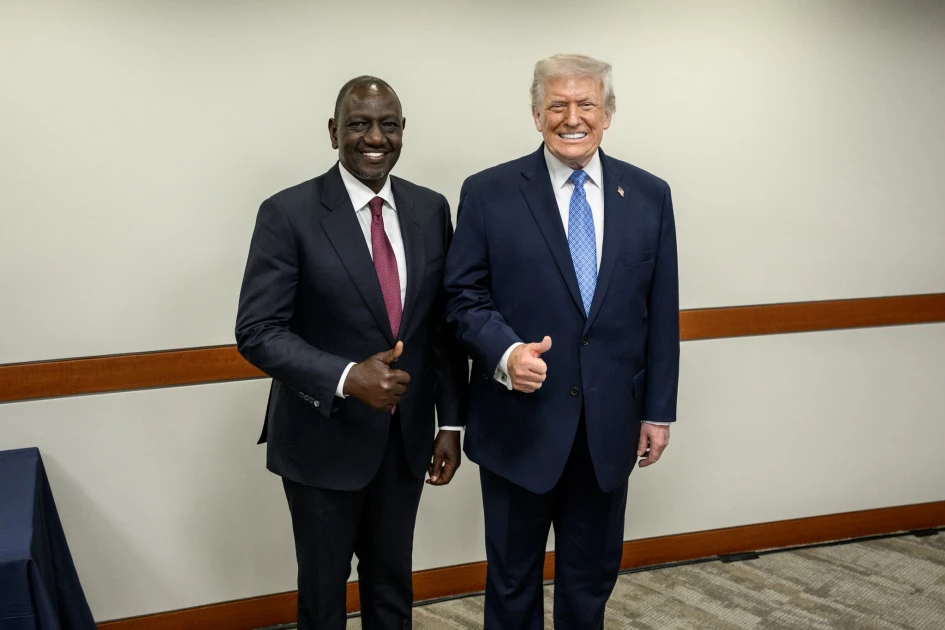

President William Ruto with US President Donald Trump after signing a health agreement in Washington on December 6, 2025. Photo:PCS

Audio By Vocalize

They are praying for the kind of health deal extended to Kenya by the United States. Data from the World Bank says Kenya spent around Ksh.11, 700 per person on healthcare 3 years ago, of which around twenty per cent or Ksh.2,393, were grants from the American government.

When the USAID went down in early 2025, it particularly exposed millions of Africans to health budget shortfalls, especially those under the management of HIV/ Aids, Malaria and Tuberculosis (TB), among other infectious diseases.

African nations will soon line up for goodies

African nations' hope is buttressed by words from the Senior Advisor for the Bureau of Global Health Security and Diplomacy at the U.S. Department of State, Brad Smith, during the award of the health sector assistance to Kenya during President Ruto’s visit to the US earlier this month.

The US government are no stranger to giving targeted aid to Kenya’s health sector. Over the years, they have given over Ksh. 7 billion to Kenya, according to Health Cabinet Secretary Aden Duale.

During the most recent visit to the US by President Ruto, the American government gave Kenya $1.6 billion (approximately Ksh. 205.9 billion). The stated goal of the funds is for Kenya to build a more resilient healthcare system for its people, integrating treatment of HIV, malaria, and TB at the primary healthcare level.

“Over the past two months, we have been engaging in very productive discussions with governments around the world about how we can maximize the impact of our health foreign assistance to save lives and build resilient local health systems while simultaneously promoting American interests abroad,” said Brad Smith.

With this broad statement, the US soft power could be seen coming back into Africa. Maybe the current administration did not like the way USAID was dispensing this power; it might have seemed convoluted, but now it is pretty straightforward. From government to government, or so it seems.

What the new system could achieve for Kenya

Supporters of the US-Kenya Health Data Agreement are upbeat that it contains a number of important and innovative provisions that will help facilitate long-term sustainability of Kenya’s health system. They assert that the funding will scale up Kenya’s health data system to ensure all the important and current data is captured immediately. This could also help Kenya to modernize its digital medical records system.

They point out that the procurement of commodities from the US to Kenya over the next several years will strengthen Kenya’s supply chain systems and institutions.

It will help Kenya to eventually absorb into its ranks specially trained employees who were formerly trained and funded by US assistance and by doing so strengthen its health sector workforce, a key factor towards achieving its dream of universal healthcare.

Those who stand for the health data system also say that this funding will develop and greatly support reimbursement of private and faith-based hospitals involved within the public healthcare sector.

When the deal is too good…

When the deal is too good, think twice! Goes the old adage. This is a caution to the receiver of any gift to think beyond the gift, for “there is no free lunch”, goes another saying. For every good deal extended to one, in a world full of self-interest and self-preservation, what the US calls today “America first”.

Kenya should think deeply about what is in the deal for the US when it awards Kenya $ 1.6 Billion for health assistance over the next five years.

Article 1 of the bilateral agreement between Kenya and the US states reads, “The purpose of this Agreement is to establish the terms and conditions under which the Government of Kenya shall provide the US Government with data, derived from Health Programs supported through the Cooperation Framework between the Government of Kenya and the US Government. Herein lies the interest of the US Government in issuing this assistance, “data” from the health sector in Kenya.

A statement released by Duale over the deal was short on details and long on the merits of the gift from America. In a rare move that should become the hallmark of all public agreements Kenya signs with other jurisdictions or entities, the health CS published the “Data Sharing Deal between The Government of the Republic of Kenya and The Government of the United States of America,” on December 4, 2025.

In a live interview on Citizen TV this past Tuesday, Duale was upbeat that the replacement of USAID within the US government, with the America First Global Health Strategy, is a positive step towards ensuring the elimination of middlemen who consumed a big chunk under the USAID tenure.

The data concerns

Digital rights advocates have descended on the agreement with kicks and blows. They claim there is little assurance of safety provided by Kenya on its nationals’ health data to the US.

The exigencies of how, where, when and the legality of the Agreement, its conformity to the Data Protection Act, and the Digital Health Act, are before the High Court.

The court on Thursday issued conservatory orders suspending the implementation of the cooperation framework between the government of Kenya and the US Government.

Concerns are high in the public domain about several issues that the published agreement has insufficiently addressed or failed to address.

Some data advocates say that the agreement is skewed against Kenya, which will provide data without any mechanism to audit, monitor, review or limit how the US government use the data.

They say ownership without control is impotent as portrayed under the agreement in paragraph 18 on “Intellectual Property.”

The critics of the agreement also point out that the seven-year window to 2032 is far too long to commit Kenya to, as credible health data, according to the Digital Health Act, 2023, is a strategic asset to the country.

By Kenya creating dashboard access, configuring rights and privileges of different entities to the data, reporting tools and backing up the system, any prolonged access from a foreign entity might pose challenges or undue disadvantages to the country.

They also say that Kenya bears all responsibilities for setting up the system, its accuracy and functionality, maintaining it, and ensuring its compliance with both Kenyan and American laws. Meanwhile, the US sits pretty waiting to log onto the system at completion with no encumbrances whatsoever.

Some critics are of the opinion that this agreement offers no guaranteed line of benefit to Kenyans, as the agreement says any accruing direct benefits from the data trove it will make available to the US might not benefit the country from research outputs from the data, technology transfer, financially and in utilizing its advanced analytics, among others.

Under paragraph 19, on the legal status of the agreement, it has stated clearly that the “agreement” is not an “international agreement” per se, and thereby does not give rise to rights and obligations under international or local laws; a position which leaves Kenya weaker and with no recourse should the agreement fall through.

Some AI experts have also pointed out that there are high risks present in giving out even de-identified data, as modern advances in data science and AI could lead to “potentially identifiable” scenarios and thereby denying citizens privacy over their data in a jurisdiction where local laws do not apply.

Legal experts in data science have pointed out that, strangely, the document does not expose the US government to accountability while it limits Kenya’s sovereignty through “a mutually written consent.”

Further, they say that the agreement, in light of its impact on the public health data collection, should be suspended to allow for the inclusion of public participation, parliamentary scrutiny and direct oversight by the office of the Data Protection Commissioner.

Data, the new Gold!

Valid and specific health data are the new frontier of valuable national assets, made possible through digitization, that could inform the decisions that nations make today for a better tomorrow.

How we treat our national data, analyze it and make use of it to inform decision-making, and then with whom we share it, is of paramount importance.

The US would not pay $ 1.6 Billion dollars if Kenya’s local health data were useless or of no concern. But herein lies the big question: “What is the US government going to do with this data, among other data it might also seek from other willing nations?”

The narrative on the streets is that American pharmaceutical companies might use the data from Kenya’s health sector in their quest towards understanding and make targeted drugs for this market.

America’s soft power creeping back

In the context of international politics and realignments, this agreement is a soft power play in geopolitics to counter the Chinese charm offensive on the continent of Africa.

By giving out grants of this nature, America is catching the attention of many developing nations, many of whom are already under heavy Chinese debts, as China rarely issues grants and would rather issue loans. A grant-dispensing, friendly America would be welcome in many countries in Africa once more.

Then there is a school of data advocates pointing out that Kenya is being subjected to data-colonialism without quite taking into perspective that data sovereignty requires economic liberation, a leverage Kenya lacks.

In this context, it helps to pick out that Sub-Saharan African countries spend about Ksh.4, 875 per capita on healthcare, while Europe spends around Ksh. 338,000 per capita on healthcare, as the US spends, Ksh.1, 935, 050 per capita on healthcare, the world’s highest expenditure on healthcare.

Solutions to help Kenya scale up

Kenya should embark on a purposeful and time-conscious journey towards building a health data system as a real option to US-led or financed health data platforms for its own research, analysis, and ultimately, for its local pharmaceutical industry and decision-making.

This might mean setting up systems that are fully locally owned so as to reduce dependence on external funding, especially if the private sector can be incorporated into the investments.

Kenya should start thinking of how to set up an Africa-centric health financing mechanism to reduce the influence and involvement of external donors. It should formulate regional collaborations with its immediate neighbors to ensure large markets are available for local manufacturing as well as technology transfer of knowledge.

Kenya’s health data deal is not an isolated case; a number of African countries will also be summoned to Washington for similar agreements that might not necessarily be in their best interests, but they will accept based on need rather than choice.

When the US hurriedly removed health programs run by the defunct USAID, it exposed the soft underbelly of many countries, which immediately got into budget shortfalls within their health sector that they could barely plug.

Today, it might be a citizen’s health data that Kenya is offering to a foreign country, and if we do not correct the ship, it might be more critical data tomorrow for a bowl of aid.

Leave a Comment